The 62-Million Ton Question: How Much AV is in Global E-waste?

With rare exceptions, the commercial AV industry has been indifferent to the sell-and-scrap pattern of technology replacement that feeds its prosperity. No one wants to talk about reducing AV product consumption, but for the most part, we are the ones who declare what is obsolete or unrepairable and then prosper from the hardware sales that replace it.

Our industry’s worst castaways include everything we produce that has a printed circuit board and passive components, millions of meters of discarded PVC-sheathed wire and cable, power supplies, lights, connectors, and more snipped plastic cable ties than we could ever count. All of it discharges into the murky river of global AV E-waste.

According to the U.N. Global E-waste Monitor, in 2022, the world generated twice the amount of electronic waste that was recorded in 2010 – almost 62 million metric tons per year. Four years from now, it is projected to be a colossal 82 million.

How much of that is commercial AV?

The answer is frustratingly vague because we have no records of what we throw away. It is likely a tiny, physical portion of the total, but the threat is not volume – it’s toxicity. The majority of toxins resides in printed circuit boards (PCBs), and at least one PCB is in every active piece of equipment our industry manufactures.

PCBs make up the highest concentration of hazardous substances within the entire e-waste stream because they contain toxic metals like lead, arsenic, mercury, hexavalent chromium, cadmium and others. A 2020 study published by the American Chemical Society, found that waste PCBs from all discarded electronics (not just AV) are 3-6% (about four million metric tons) of the total global e-waste volume. It concluded that those four million tons are responsible for 70% of the toxicity in authorized landfills, and 90% in illegally transshipped e-waste dumped in developing countries.

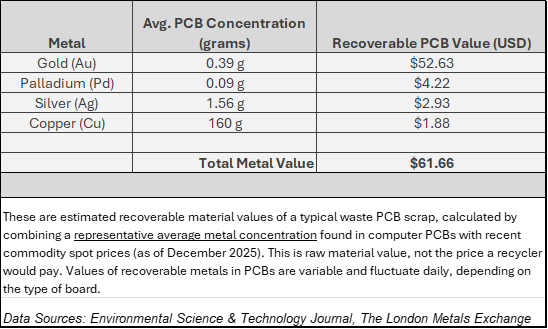

And in a weird Bizzaro relationship to the 70% toxicity, metals industry research estimates that PCBs also contain over 70% of the value of recoverable precious metals, especially from high concentrations of gold (see Table 1 below).

Table 1: Estimated Recoverable Material Value of PCB Scrap

E-waste recycling is not an act of benevolence; it’s a for-profit business...

Recycling is the obvious solution to e-waste, and doing it ethically and responsibly is not cheap. In fact, recycling a discarded flat panel is five to ten times more costly than just dumping it in a landfill.

Recyclers need to make a profit (that's why you might pay for a recycling pick-up), and the material they retrieve goes through a complex set of transactions. Unwanted electronics are transported to a facility where the protected workers safely disassemble components, identify, and separate them into basic materials of plastic, glass, metal, and recoverable metals. Whole components that can be resold, like microchips, are also isolated and categorized.

Different regions around the globe use varying methods for categorizing e-waste, but the recycling industry typically cubby-holes it within several general categories (like screens & monitors, small equipment, large equipment, IT and telecommunications equipment). Products that share a category are assumed to have similar weight and lifespan; however, while smaller AV components might fit into 'small equipment' and networked systems into 'IT,' these groupings are too broad to determine the specific types and amounts of AV waste.

When a responsible recycler dismantles an electronic device, the parts can end up in non-descript piles of printed circuit boards, plastic, metal and scrap components, where the pieces of a Crestron processor are indistinguishable from those of a Dell PC or the control panel of a Peloton bike. After sorting and shredding the boards, the components are then sold and sent to specialized facilities like a smelter or hydrometallurgical plant for the recovery of precious and base metals.

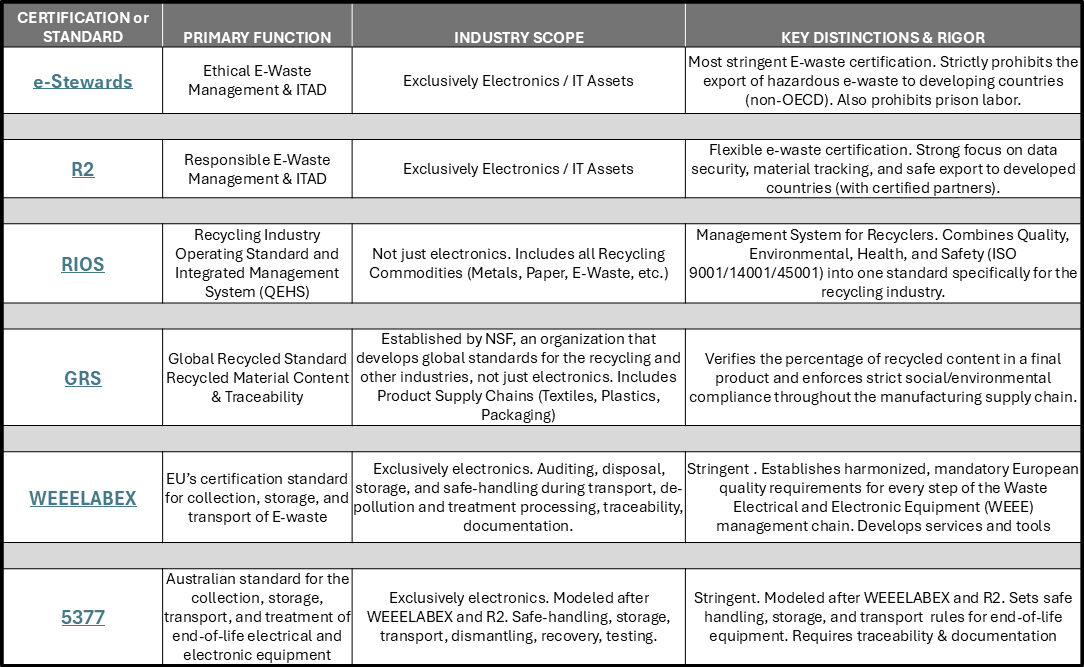

But not all recycling is good recycling. According to The Electronics Reuse and Recycling Alliance (TERRA), if a recycler isn't e-Stewards or R2 certified, they aren't meeting the toughest standards. To keep their certifications, recyclers' operations are regularly checked by outside auditors to prove their processes are sustainable, protect the environment, address the impact on human health, and conserve natural resources.

There are other global electronic waste recycling standards which alone don't match the strict requirements of e-stewards or R2 certifications, but certifications and standards are two different categories, and recyclers may have multiple credentials depending on where they are licensed to operate (Table 2):

Table 2: Comparison of E-waste Recycling Certifications and Standards

Being non-certified does not inherently mean a recycler lacks integrity, but it signifies a crucial difference in accountability, standardization, and verification of their processes. In other words, nobody's watching.

Bad apples...

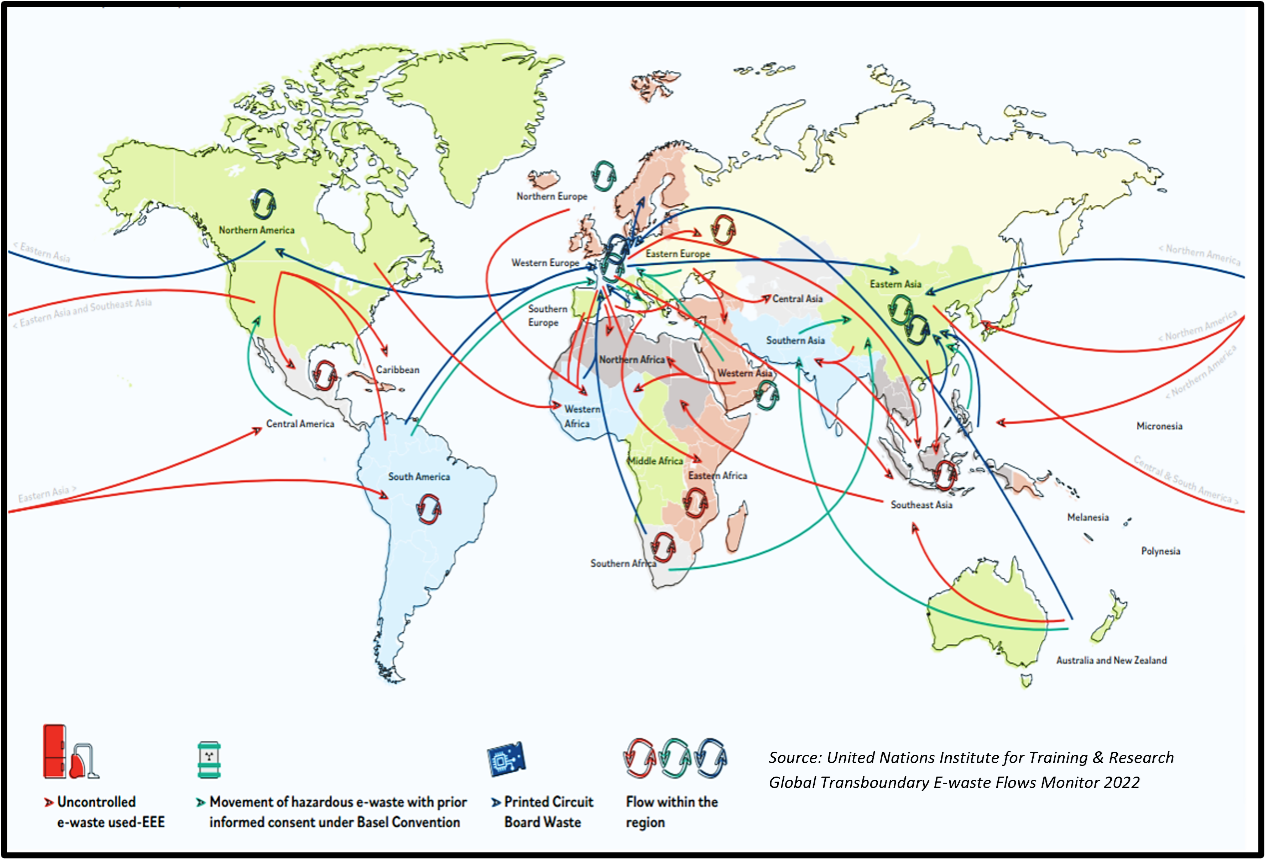

There are illegal E-waste exporters variously called "Transhippers, E-waste Traffickers, Waste Brokers and Sham Recyclers," who, despite international law, ship e-waste to developing countries (Figure 1) where unskilled and unprotected workers who are mostly children, melt circuit boards, soak microchips in acid, and burn plastics in open pits to retrieve precious metals. The impact on their health and their communities, as well the soil, air, water, is devastating. Burning insulated wire to retrieve copper can release up to 100 times more cancer-causing dioxins than other waste. Toxic residue makes its way to the water supply, marine environments, agricultural land and ultimately, the food chain. The more we rely on revenue from technology obsolescence and replacement, the more discarded AV technology may become part of that undocumented waste.

Figure 1: Global Transboundary E-waste Flows

What’s in your rack?

When flat panels began replacing CRTs in the mid-2000’s, few of us knew that the millions of old monitors we threw away had glass tubes shielded by up to four pounds of toxic lead oxide. How many ended up smashed in dumpsters and buried in landfills? Should manufacturers have provided some guidance about their product disposal?

With a few laudable exceptions, manufacturers have historically detached themselves from their products once they reached the end of their operational lives, and it is unlikely to expect revelations of intellectual property by identifying what is in their internal componentry. Without that information, though, the burden of validating recycling value, or determining responsible disposal is on the end-user, and we need a simple solution to document what we discard before it ends up in an e-waste salad.

Toward A Potential Solution...

Since the industry's business model relies on the customer not holding onto old equipment indefinitely, tracking its disappearance could actually benefit new sales, so end-of-use information may be valuable to manufacturers who would support something like the following concept.

Once the responsibility for a product's life cycle shifts to the end-user, they are the only ones to know when it's removed. Most large AV users, like universities, corporations or healthcare systems will document assets that are retired from use or fully depreciated. That could work with a tracking concept from IT recycling, called a "Certificate of Destruction," which is documentation that important data or devices have been destroyed. An AV manufacturer could assign a unique ID to a device which can be part of the customer's asset record. When a technician or customer pulls the equipment, they scan a QR or barcode which marks it as "removed" or end-of-life, and links it to disposal fields in the organization's asset-management software for an audit trail. That record, minus proprietary information, can be anonymously shared with a cloud database where the component becomes traceable from the factory floor to a recycling facility. It can also be a resource for manufacturers to understand the true lifespan of their products and the raw materials flowing back into the system.

Of course, there are a bunch of holes in the above. The deepest is that every organization uses different asset management software. Also, there needs to be an incentive for certified recyclers to scan the ID upon material receipt to close the loop. All of this is a small part of a needed, larger dialogue, so please add your comments and ideas in the field below. If your organization is already tracking its discarded electronics, let us know how. Maybe we can figure out where all of our stuff is going and begin reducing our industry's environmental impact.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on AVIXA Xchange, please sign in